Meaning of 'Neighbourhood'

In its original sense, a neighbourhood comprised neighbours - people who lived near one another, who would know each other and share neighbourly relationships. According to the Wikipedia (6th May, 2007), “……traditionally, a neighbourhood is small enough that the neighbours are all able to know each other…. although this term may also be used across much larger distances in rural areas.

But in present use, a neighbourhood can also mean a geographically localised community, a residential district, located within a larger city, town or suburb. Although the residents of a given neighbourhood may be called neighbours, in practice, they may not know one another very well at all. This newer meaning of neighbourhood can be traced back to Clarence Perry and his idea of the ‘neighbourhood unit’.

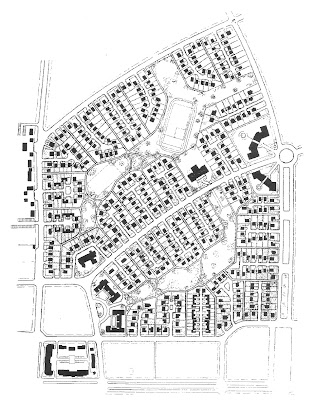

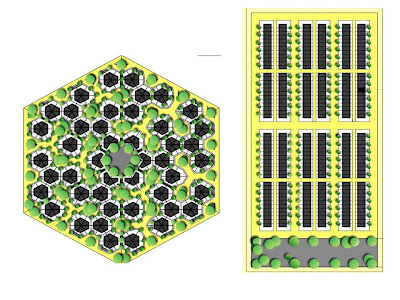

Clarence Perry, a sociologist and member of the Regional Planning Association conceived “The Neighbourhood Unit – A Scheme of Arrangement for Family-Life Community”. Perry’s concept was part of an extended process of regional planning for the New York area done between 1922 and 1929. (Southworth, Eran). His aim was to find a fractional urban unit that would be self- sufficient yet related to the larger whole. He proposed planning principles for the comprehensive layout of residential areas:

- Population of about 3000 to 10000, being the size that would have its own elementary (primary) school of about 1000-1600 children.

- The school, along with other communal facilities like hall, library and church would be centrally located.

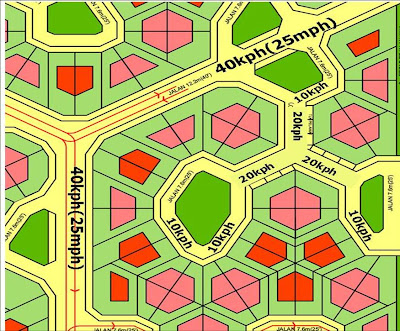

- The neighbourhood would be ringed by arterial roads; the arterial road was to discourage through traffic into the residential neighbourhood, but also to give a distinct boundary to the neighbourhood.

- The shopping area would be at the periphery of the neighbourhood, along the arterial road.

- There should be a system of small parks and recreation areas to serve the children and youth. He suggested 10% of the total area to be a reasonably good provision.

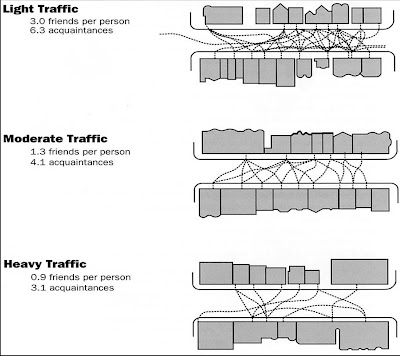

- The roads within the neighbourhood would be the small local roads in front of the houses and collector roads that joined the local roads to the arterial roads, the size of the roads being just big enough for the traffic load.

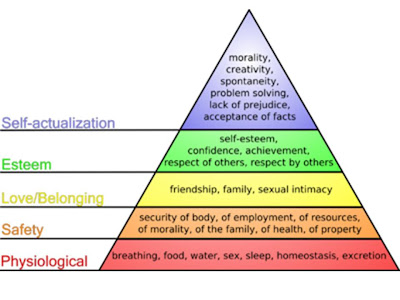

Perry wrote ‘Follow these prescriptions and you would have a neighbourhood unit that would stand out geographically as a distinct entity, and residents would feel a sense of belonging to that neighbourhood. When it has complete equipment from the vicinity needs of its families; when the public services are nicely adapted to population requirements and all its component parts are integrated by a comprehensive plan – then you have a neighbourhood community that is bound to be marked because the esteem in which it is held by its residents’.

Perry framed the concept of the neighbourhood unit after experiencing the benefits of a well planned suburban resident of Forest Hill Gardens on Long Island, a model of new suburban development. These suburbs, originally small and self contained helped to re-create a consciousness of something that had been lost in the rapid growth of cities – the sense of neighbourhood found in villages, and small towns. What Perry did was to make explicit, in a better defined structure, the life he had found rewarding.

Perry’s framework for the neighbourhood, brought within walking distance all the facilities needed daily by the home and school, and to keep outside this pedestrian area the heavy traffic arteries carrying people or goods that had no business in the neighbourhood. No playground, primary school or local shopping area should be more than a quarter of a mile (0.4km) from the houses they served. The population and geographical size was limited. Perry placed the population at 3000 to 10,000: large enough to supply a full variety of local services. The periphery would be physically defined by main roads or a green belt.

Perry had identified the fundamental social cell of the city as the neighbourhood.

(Lewis Mumford).

This idea of neighbourhood is not all wrong (later I shall return to it to see how it may help us design ‘block’ and ‘town neighbourhoods’ which might contain more than a thousand people). But it should not preclude us from using the word ‘neighbourhood’ in its original sense: a small community where people know each other. Many have explored the idea of the small community in environmental design but have used terms like ‘sub-neighbourhoods’ or ‘homezones’. Other relevant words are ‘semi-public’ or ‘semi-private’ areas.

A website based on the work of Christopher Alexander, author of Pattern Language (1977) says: ‘In our view, almost any part of the environment may be viewed as a neighborhood. A neighborhood can be very small (less than an acre), or quite large (hundreds ofacres). It can be a hospital, a business, a group of workshops, a place where people live and work. A neighborhood is any group of people and their activities, animals, buildings, plants, and public space. Neighborhoods of different sizes are usually nested inside one another’.

I will just use the word neighbourhood, and qualify it with prefixes like ‘courtyard’, ‘cul-de-sac’, ‘block’ or ‘town’; and, from here on, without parentheses.

Just as Perry asked how we should design the neighbourhood unit, we ask, how we should design small neighbourhoods.