Provide an Arena for Social Contact

When pre-requisite conditions like safety and comfort have been met, we can look at the function of the space just outside the home as a social space. Can environmental design render this space more conducive to social use? In his book “Life Between Buildings”, first published in 1971, Jan Gehl saw outdoor activities as an important precursor of contact and social relationships. He argued that there were three types of outdoor activities: necessary activities, ‘optional’ activities and social activities. The frequency of the necessary activities, like going to work, shop and other activities that people must do in everyday life, did not vary whether the contact at a modest level

• starting point for contact at higher levels

• maintaining already established contact

• a source of information about the social world outside

• an offer of stimulating experience

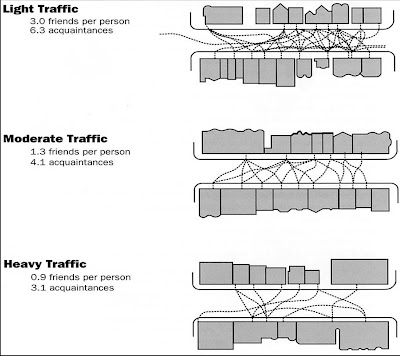

The effect of the quality of the environment on the level of outdoor activity in it is clearly shown in a study which compared the frequency of outdoor activities and contacts between friends in three parallel streets in San Francisco. Registration of frequency of occurrence of outdoor activities (dots) and contacts between friends and acquaintances (lines) in three parallel streets in San Fransisco.

Top: Street with light traffic

Center: Street with moderate traffic.

Bottom: Street with heavy traffic. Almost no outdoor activities and few friendships and acquaintances among the residents.

Factors that encourage outdoor activities

So what are the factors that planners need to consider? For the small neighbourhood they include designing for the human scale, concentrating focus rather than diffuse dispersal, integrating different functions and characteristics rather than segregation, and soft edges.

Human Scale

Anthropologist E. T. Hall wrote "The Hidden Dimension" which developed and popularized the concepts of personal space - the distance between men in the conduct of daily transactions, the organization of space in his houses and buildings, and ultimately the layout of his towns."

Hall defined and measured four interpersonal "zones":

- intimate (0 to 18 inches)

- personal (18 inches to 4 feet)

- social (4 feet to 12 feet)

- public (12 feet and beyond)

In "The Hidden Dimension" he famously observed that the precise distance we feel 'comfortable' with other people being near us is culturally determined: Saudis, Norwegians, Milanese and Japanese will have differing notions of 'close'.

In ‘The Hidden Dimension’ Edward Hall defines distances in terms of human communication within European and American culture:

- Intimate distance of below 18 inches (<45cm)>

- Personal distance of 18 inches to 4 feet (45cm to 1.2m) is the conversation distance between close friends and family. This is the distance between people around a dining table.

- Social distance, 4feet to 12 feet (1.2 to 3.6m), is the distance for ordinary conversation between friends, co-workers, neighbours, etc.

- Public distance of more than 12 feet (3.6m), is defined as the distance used in more formal situations, around public figures or in teaching situations with one way communication or when someone wants to hear but does not wish to get involved.

This perspective gives a human dimension to distances and scale. In old cities narrow streets and squares, the buildings and the people in it are experienced at close range and considerable intensity and are perceived as intimate, warm and personal. Conversely many modern projects with large spaces, tall buildings and wide streets are felt to be cold and impersonal.

There must also be time to see and process visual information. Human sensory perception are mainly designed for walking or running speed (3 to 9kph). As the speed is increased, the possibility of discerning details and processing social information drops sharply. On the highway, signs and billboards have to be huge and bold to be seen. Buildings are comparatively large and details are few since they these cannot be seen anyway. Faces and facial expressions of people are too small to be perceived at all.

Apart from scale and speed , other factors that inhibit or encourage contact are sightlines– in terms of barriers or walls, multiple levels or orientation.

| Isolation | Contact |

| Walls | No walls |

| Far | Near |

| Fast | slow |

| Multi-level | One level |

| Facing towards | Facing away |

Much of town-planning is concerned with the sub-division of land into different functions and then creating circulation routes connecting them. The functional city comprised mono-functional zones. Work separated from home, separated from recreation; the rich separated, separated from the middle class, separated from the poor. University towns, administrative capitals, retirement villages perhaps brought some benefits of efficiency but pay the price of being isolated from other groups in society. By contrast, in traditional towns, rich and poor, merchants and craftsmen, young and old had to live and work side by side. In ‘The Death and Life of Great American Cities’ Jane Jacobs pp153- 177, is a cogent argument of how diversity increases the range of hours streets, shops and city amenities are frequented. By this convenience, liveliness and variety of choice are increased. In an offices only district, the streets are busy only during office hours but deserted otherwise. In areas where residential and workplaces are mixed, the streets are occupied throughout longer hours to the benefit of businesses.

Another aspect of integration is that between vehicular traffic and pedestrians. He argues that separation of traffic and pedestrians like in the Radburn model diffuses outdoor activity. It becomes duller to drive, duller to walk, duller to live along because a significant number of people in transit are now segregated away. He advocates the Woonerf as a better solution: where vehicular traffic moves at pedestrian speed, the arguments for separating playing, walking and the areas for traffic lose their validity.

Concentration

Parallel to the development of functionalistic town-planning is the spread of low-density, single family homes in the suburbs made possible by the increased use of cars. In these areas desirable conditions have been created for private use by the family, but residential areas have a diffuse structure and uncertain boundaries, It is not clear where the individual belongs, where the neighbourhood ends. The design of the residential streets rarely takes into account where and how communal activities can take place. The shopping mall becomes the main place for contacts. Conversely designs of courtyard housing can provide a focus for small community activities. With this architectural form, activities that originate from the area in front of the houses at the house entrances can grow from the edge to the middle.

People are attracted to other people

A lively place attracts more to come, An illustration of this was found in studying the pattern of children’s play in areas of high and low-density housing in Denmark. In the terrace house areas, where the ‘density’ of children was twice the density of detached houses, four times the number of play activity was found. On the other hand, a dull, deserted place remains deserted.

Children’s playground equipment provides a good excuse for children to come out. A child playing by himself can easily attract other children. They socialize most easily. Watching children play is a pleasurable entertainment for most adults, and in this way, invite parents to come out too.

Soft Edges

A study of the frequency and duration of all types of activity on twelve residential streets in Waterloo and Kitchener, Ontario showed that although ‘come and go’activities account for more than 50% of the total number of activities happening on 12 streets surveyed, stationary activities are the ones that bring life to the streets. Because of their duration, they account for an impressive 90% of all time spent on the streets.

In a study of two parallel streets in Copenhagen, a hard edge street, suitable only for brief comings and goings, was compared to a soft-edge street - where it was easier to go in and out where there were suitable areas for stationary activities and which provided something to do in front of the house – the soft-edge street had three times more activities in the course of a normal day compared to the hard-edge street.

These houses were moderately close to together and have semi-private porches facing the street. “The study of row-house areas with semi-private front yards in Canada …and Scandinavia emphasize that even very small outdoor areas placed directly in front of houses can have a far greater and substantially more faceted use than larger recreational areas that are more difficult to reach. This does not mean that that areas for sports, green lawns and city parks are in any way superfluous, but it means that in all cases there should be areas and resources set aside to provide “immediate” recreational areas. The few well-designed square feet next to a dwelling will most often be more useful and more used than the larger areas farther away.”

No comments:

Post a Comment