Protection from Traffic

Another aspect of security is that of safety from traffic, and this has been an issue from the earliest days of the private car. In the US for instance, car ownership rocketed in the early 1900’s when prices became affordable, a good road system was developed, and new innovations that made driving easier and safer. The private car had a great impact on the social, economic and political structure of modern society. It brought new opportunities to individuals and families, and allowed for the development of new suburban communities away from the city center and public transport routes. Street design to cater for the private car became a key issue in planning and development, and a determining factor in shaping he pattern of the environment.

There was resistance against the growing influence of the motorcar. Clarence Stein, a planner wrote:

American cities were certainly not places of security in the twenties. The automobile was a disturbing menace to city life in the USA –long before it was in Europe….The flood of motors had already made the gridiron street pattern , which had formed the framework for urban real estate for over a century, as obsolete as a fortified town wall…..The checkerboard pattern made all the streets equally inviting to through traffic. Quiet and peaceful repose disappeared along with safety. Porches faced bedlams of motor throughways with blocked traffic, honking horns, noxious gases. Parked cars, hard grey roads and garages replaced gardens.(Clarence Stein)

Clarence Stein and his colleague Henry Wright went on to design "a town for the motor age" in Radburn, New Jersey. They pioneered the concept of separating pedestrians from cars. The Radburn plan places the housing on long narrow cul-de-sacs for car access. Footpaths were placed at the opposite side of the houses providing pedestrian access to central green areas and communal facilities like schools. Thus, children could walk to school and play areas without crossing any street. Radburn introduced the largely residential "superblock" and had some of the earliest cul-de-sacs in the United States(Southworth and Eran).

The "town for the automobile age" did not take into account just how popular the automobile was going to be. Most of the Radburn homes are on small cul-de-sacs ending at a park; this design was intended to accommodate automobiles without requiring them. As latter 20th century economics and practice resulted in families with multiple cars, congestion arose on the cul-de-sacs where parking outside of one's own driveway was limited. (Cited from Wikipedia 7th May 2007).

Elsewhere in America, the pervasiveness of the private car unleashed forces that created highways and real estate developments into the open country that urban sprawl that typifies much of the country’s landscape today.

As soon as the motor car became common, the pedestrian scale of the railroad neighbourhoods disappeared, and with it, most of its individuality and charm. The suburb ceased to be a neighbourhood unit: it became a suffused low density mass. But the motorcar had done something more than destroy the pedestrian scale, it either doubled the number of cars needed per family, or it turned the suburban wife into a full time chauffeur. Cite Lewis Mumford,The City in History, 1961, pp 504-506.

The priority given to vehicles also posed problems of safety. As James Howard Kunstler puts it in The Geography of Nowhere: The Rise and Decline of America's Man-made Landscape: “The traffic engineer is not concerned about the pedestrians. His mission is to make sure that wheeled vehicles are happy. What he deems to be ultra-safe for drivers can be dangerous for pedestrians who share the street with cars. Anybody knows that a child of eight walking home from school at three o'clock in the afternoon uses a street differently than a forty-six-year-old carpet cleaner in a panel truck. After decades of preoccupation with the needs of the carpet cleaner, it's time to rethink streets and roads with the needs of that eight-year-old in mind.”

Shared Streets

Whilst the Radburn model separated cars from traffic, another model emerged in Europe in the 60’s. The model is one of integration, with an emphasis on the community and the residential user. Pedestrians, children at play, bicyclists, parked cars, and moving cars all share the same street space. Even though it seems the these uses conflict with one another, the physical design is such that drivers are placed in an inferior position. Such conditions are naturally much safer than the conventional street design. By redesigning the physical aspects of the streets, the social and physical public domain of the pedestrian is reclaimed.

The philosophical roots of the shared streets concept can be found in a report, Traffic in Towns, in 1963 by an architect and traffic engineer, Colin Buchanan and his team. They were able to see the conflict between providing for easy traffic flow and the maintenance of the residential and architectural fabric of the street. They suggested segregating traffic and pedestrians completely in certain environmental areas, allow mixing of vehicles and pedestrians in others, The concepts of ‘traffic intergration’ and ‘traffic calming’ were not initially well received in Britain , but they proved to have more impact in the Netherlands, where it inspired Niek De Boer, professor of urban planning at Delft University, to design streets so that motorists would feel as if they were driving in a ‘garden’ setting, forcing drivers to consider other road users. De Boer named the street “woonerf’ or ‘residential yard’. The Delft Municipality decided to experiment with this idea and its success spread throughout the Netherlands in the form of design standards and traffic regulations.

Shared streets integrate pedestrian activity with vehicular movement on one shared surface, but the pedestrian and bicyclist have priority over the car. These streets are often at the same grade as curbs and sidewalks. Cars are limited by law to a speed that does not disrupt other uses of the streets (usually defined as walking speed). To make this lower speed natural, the street is normally set up so that a car cannot drive in a straight line for significant distances, for example by placing planters at the edge of the street, alternating the side of the street the parking is on, or curving the street itself. Other traffic calming measures are also used. However, early methods of traffic calming such as speed humps are now avoided in favor of methods which make slower speeds more natural to drivers, rather than an imposition.

Even though many people were afraid that the mixing of vehicles and pedestrians and play area on one surface could be dangerous, studies that have been done in the Germany, Denmark, Japan and Israel show that there are 20% fewer accidents in shared streets and over 50% fewer severe accidents compared with standard residential streets.

The most prevalent traffic accidents on standard residential streets are children-related accidents. According to a study in England, half of all road accidents with children under five occur within 100 meters of their homes. The same survey showed that very few such accidents occur on streets with restrictive devices and shared streets or cul-de-sac designs. The safety results in Europe and Asia appear to be similar.

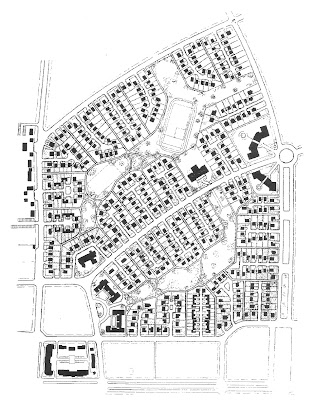

The Honeycomb design can incorporate the design features of the shared street. However, even without traffic legislation to impose maximum speed in these areas, and the adoption of a single surface for pedestrians and vehicles, some of the effect of the shared streets in terms of safety and security can be achieved.

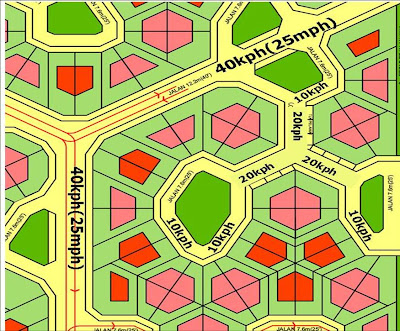

A car entering a Honeycomb development would have to slow down at the entry junction but would not have much opportunity to regain speed – the longest straight stretch of distribution road being less than 150 meters (500’). After slowing down to enter a cul-de-sac, the longest straight stretch of road is only 25 meters (80’). House entrances are off a looping road where cars have to slow down further.

We would target the following vehicle speeds by placing further traffic calming measures, notably introduction of rough strips of pavement across the roads at strategic locations:

• Distribution road: maximum 40 kph

• Straight stretch of connecting roads into cul-de-sacs: maximum 20 kph

• Looping road in courtyard: maximum 10 kph

Walking speed is about 6kph.